A few months later, CBS reported on a "Monster 'Freak' Storm" (wrong) that brought 230 MPH winds to Iceland (wronger). Two years after that, CBS reported Hurricane Nate "touched down" (wronger-er) on the northern Gulf Coast, bringing flooding to the Mississippi River community of Mobile (wrongest).

And then there's Maude!

Today we learned about a "rare meteorological phenomenon" known as a "snow firehose."

Who knew?

I've used plenty of cheeky hyperbole in my oddball blogging adventures. I peppered The Vane with dorky phrases like "wind bagel," "dangerous sky onion," and "Polar Flortex" to describe annular hurricanes, large hail, and a storm off Florida, respectively. It was meant to be hokey!

But CBS News, bless its heart, isn't in on the joke. We've graduated from sideways tornadoes to a snow firehose. Granted, I'll give the reporter the benefit of the doubt that somewhere in his reporting, a meteorologist may have analogized the thick, intense band of lake effect snow plastering northern New York as akin to a firehose.

Nowhere, though, is it ever an actual term used for actual events. Go ahead. Google it. If you filter out February 27-29, it's nearly impossible to find any mention of "snow firehose" that doesn't loop back to CBS's report on Friday.

|

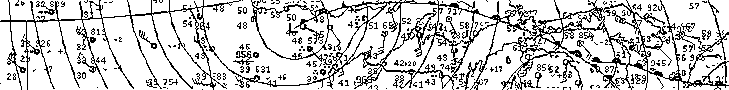

| The band of lake effect snow over Watertown, New York, on February 28, 2020. (Gibson Ridge) |

Lake effect snow can occur when wind blows cold air over relatively warm waters. The warmth of the water warms up the air immediately above the surface of the lake. This warm air rises through the colder air above through convection, creating bands of snow that blow ashore. The resulting lake effect snow can develop as thin bands that produce a broad swath of accumulation (common on Lake Michigan), or it can form into a solid band that traverses the length of the lake and plasters a small area with a lot of snow, which is common on Lakes Erie and Ontario.

The latter process, called single-band lake effect snow, is what we've seen in northern New York for the last couple of days. A long, cold fetch across an ice-free Lake Ontario allowed an intense band of snow to ride up the Tug Hill Plateau and drop several feet of snow. In fact, the orientation of the winds allowed for several bands of snow to set up across Lakes Superior, Huron, and Ontario, giving the appearance on radar that it was a single band of snow stretching from one body of water to the next.

Single-band lake effect snow is relatively common and it's often intense, dropping several inches of snow an hour and occasionally producing lightning. This was a particularly hefty band that dropped four feet of snow in some higher elevations. There's a reason northern New York isn't exactly known for sunbathing in the wintertime.

It's okay to refer to this as a "snow firehose" as an analogy to explain it, but it's not a term anyone uses seriously as the report reports. News organizations have got to be more precise and accurate in their reporting of events like lake effect snow. Meteorology is a science, after all, and goodness knows we don't need another ripe-for-TV buzzword at the expense of the facts.

[Screenshot: CBS News]

You can follow me on Twitter or send me an email.

Please consider subscribing to my Patreon. Your support helps me write engaging, hype-free weather coverage—no fretting over ad revenue, no chasing viral clicks. Just the weather.

Please consider subscribing to my Patreon. Your support helps me write engaging, hype-free weather coverage—no fretting over ad revenue, no chasing viral clicks. Just the weather.