Hurricane Laura made landfall in southwestern Louisiana early Thursday morning with maximum sustained winds of 150 MPH, making it the strongest hurricane on record to hit this stretch of the Gulf Coast. The storm left widespread damage in its wake as hurricane force winds dug deep into the heart of inland Louisiana. While it looks like the region avoided the absolute worst-case scenario when it comes to storm surge, it seems to have been by just a couple of miles.

The Damage

Daylight revealed tornado-like damage in and around Lake Charles after an extended period of intense winds in the eyewall of a high-end category four hurricane. Many homes and businesses were heavily damaged or destroyed by the storm. Social media is full of residents and storm chasers posting pictures of homes missing roofs and walls. The transmitting tower at KPLC-TV toppled into the studio where a crew would've been covering the storm had they not evacuated.

The Weather Channel's Stephanie Abrams and Jim Cantore covered the storm from two adjacent casino resorts on the northern side of Lake Charles. The sound of the wind howling through both of their hotel lobbies—the ghostly whistling in Abrams' hotel and the chainsaw-like vibrations in Cantore's hotel—was one of the most gripping moments of storm coverage caught in a long time.

|

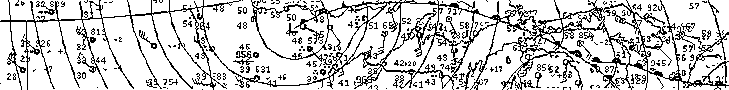

| Source: GR2Analyst |

The National Weather Service in Lake Charles sustained damage around its property, including the complete loss of the office's Doppler weather radar. The scan above was the last image transmitted by the office's radar last night, taken just as the center of the eye made landfall. As far as I can find, this is the fourth WSR-88D site destroyed by a storm, joining radars in Texas (supercell, 2001), Nevada (windstorms, 2008), and Puerto Rico (Maria, 2017).

Communications went down before the storm shredded the radar to pieces, so they might have a few more scans of the storm saved somewhere before the radar failed. It's probably going to be a while before they can get a replacement radar online. Nearby radars in Houston, Fort Polk, and New Orleans will have to cover the northwestern Gulf Coast in the meantime.

Wind damage extended far inland through Louisiana, eastern Texas, and now into southern Arkansas. Data collected by PowerOutage.US showed nearly 30 percent of all electric customers in Louisiana without power this afternoon, including almost every home and business around where the storm made landfall.

All told, there are about 608,000 electric customers in Louisiana, 222,000 customers in Texas, and 36,000 customers in Arkansas without power around 2:30 PM CDT on Thursday. Many of these outages will last a week or longer, especially where the storm produced hurricane force winds. This kind of extended outage is going to be especially tough in a region that's still steeped in the heat and humidity of summer.

The full extent of the storm surge won't be clear for a while because the largest water rise likely occurred over low-population areas southeast of Lake Charles. A destructive surge pushed into Cameron, Louisiana, where most buildings were heavily damaged or destroyed by winds and water. The above video shows some helicopter footage shot above Cameron today. It's likely a similar story in Creole and Grand Chenier, coastal communities that experienced the hurricane's eastern eyewall.

|

| Source: USGS |

Given the path of the storm, it's probable that Cameron missed the highest surge and the worst occurred east of Calcasieu Lake. I bounded the area on a map of USGS sensors—you'll notice there aren't any sensors where it's likely that the worst surge occurred.

We may never know the true extent of the highest storm surge from this hurricane. That's not necessarily a bad thing, of course, since it means the worst happened out of the way where there aren't many structures to take a tape measure and record the high water mark.

There's an inevitable discussion today about whether or not the blunt wording used ahead of the storm—"unsurvivable storm surge"—was crying wolf. We see it after almost every major weather event. This kind of manufactured erosion of trust could do harm going into the heart of an active hurricane season.

It's easy to second-guess forecasts and the sternness of warnings in hindsight. We'd have a much different situation right now if the storm had wobbled just a few miles to the west, putting the eastern eyewall over Calcasieu Lake and pushing a huge surge into Lake Charles. That didn't happen, thankfully, so outside observers today feel pretty comfortable asking if warnings were over-the-top or worth it.

I've always sensed that the "Bust Or Validated?" debates after big weather events are tinged with a wisp of disappointment that flows just beneath the surface; discussions typically instigated by folks who seem crestfallen that the worst didn't happen and there's no footage of an immense surge washing away what the wind couldn't dislodge.

The difference in this case was just a few miles, just one wobble of the eye. The strong language was absolutely warranted. Lake Charles missed the worst surge, but communities along the coast didn't, and they're probably pretty grateful that they heard the warnings loud and clear and left. Either way, I'm sure that the folks in southwestern Louisiana who will spend the next few weeks sweating in the dark will be very interested in this discussion as they try to rebuild their homes and lives during a down economy and a raging pandemic.

Rain, Wind, and Tornadoes

The center of Tropical Storm Laura is located over southeastern Arkansas this afternoon. Laura and its eventual remnants will get caught up in the jet stream, turning east and racing toward the Mid-Atlantic through Saturday. The heaviest rain is falling right now across Arkansas, where some communities could see more than half a foot of rain. This much rain this fast will lead to flash flooding in vulnerable areas.

We'll have to watch the storm closely as it picks up speed and heads out toward the Atlantic. The combination of gusty winds and heavy rain could lead to downed trees and power lines across the Tennessee Valley and the Mid-Atlantic over the next couple of days. There are some hints that the storm will pick up a little strength over land as a result of its interaction with the jet stream; this would increase the chances for gusty winds that could damage trees and lead to power outages.

A threat for tornadoes will follow the system out to the Atlantic Ocean. The Storm Prediction Center's forecast shows a risk for tornadoes in the Midsouth on Friday, moving into Virginia and North Carolina by Saturday. A risk for severe weather also exists up near the Great Lakes on Friday and Saturday; this isn't related to Laura, but it's worth paying attention to nonetheless.

The remnant system—whether it's still Laura's circulation or if it absorbs into another low nearby—will strengthen over the western Atlantic early next week and head toward the Canadian Maritimes, bringing these provinces some gusty winds and heavy rain.

Don't Look Now...

|

| Source: NHC |

It seems like we've lived through a full hurricane season already, but the climatological peak of the season doesn't happen for another two weeks. We've got a long way to go and there are already a few areas of interest far out in the Atlantic that we'll need to pay attention to over the next week.

Now that we have a fresh reminder of how much widespread damage a landfalling hurricane can do—and how far inland the impacts can spread!—this is a great time to make sure you're prepared to get through the rest of the season.

[Satellite: NOAA | Video: WXChasing on YouTube]

You can follow me on Twitter or send me an email.

Please consider subscribing to my Patreon. Your support helps me write engaging, hype-free weather coverage—no fretting over ad revenue, no chasing viral clicks. Just the weather.

Please consider subscribing to my Patreon. Your support helps me write engaging, hype-free weather coverage—no fretting over ad revenue, no chasing viral clicks. Just the weather.