The Setup

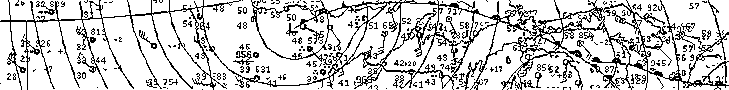

A severe weather event unfolded across the southern United States beginning on April 9 and continued through April 10. The Storm Prediction Center issued a moderate risk for severe weather in anticipation of a strong squall line developing in Arkansas and Louisiana that would eventually move east toward Mississippi and Alabama.

The storms played out more or less as forecasters expected, with plenty of reports of strong wind, large hail, and occasional tornadoes scattered across the areas outlined in the agency's outlook. During a severe weather event like this, you'll often hear during severe weather coverage that the storms could come in multiple rounds. Severe weather outbreaks in the southern United States often happen in two rounds, with one batch of discrete thunderstorms developing in the unstable air ahead of the squall line, followed by the squall line itself.

If there's enough instability and wind shear present, those discrete thunderstorms can develop rotating updrafts, becoming supercell thunderstorms. This one-two punch is the situation that led to enormous hail falling on Orange Beach, Alabama, during the April 9-10 severe weather event.

The Hailstorm

A supercell that developed over the northern Gulf of Mexico came into good view of the radar in Mobile, Alabama, around 2:30 AM CDT. The supercell was rather mean looking when it was over the open water, with strong rotation showing up on radar's velocity (wind) data and a pronounced hook echo on reflectivity (precipitation) imagery.

Hailstones can grow inside of a thunderstorm as long as they remain within reach of the updraft and the updraft can sustain their weight. A stronger updraft, like one you'd find in a supercell, can support larger hailstones. Radar revealed that this supercell developed a huge hailcore as it reached peak strength over the northern Gulf of Mexico.

You can see the hailcore in 3D radar imagery just before the storm crossed the coastline. This radar image is from around 2:56 AM:

In this image, the word "WEST" is directly over Mobile Bay, and the thunderstorm is just about to cross the coastline into Baldwin County. I've dimmed all the colors on the radar's color scale except for the highest returns, highlighting the thunderstorm's huge hailcore.

The supercell rapidly weakened and lost its structure as it moved from the water over land. This sudden weakening caused all of that enormous hail in to fall to the ground in unison, leading to a tremendous hailstorm in communities near the coast. An animated look at that 3D radar imagery shows the hailcore rapidly falling out as the storm moves ashore:

The National Weather Service in Mobile issued a severe thunderstorm warning as the supercell neared the coast in southern Baldwin County. The initial warning at 2:50 AM called for quarter size (1.00") hail. An updated warning issued at 3:06 AM called for hail up to 2.00" in diameter, which is roughly the size of an egg you'd buy at the store. Forecasters upped the potential to "tennis ball size" hail, or 2.50" in diameter, by 3:34 AM as the storm pushed inland.

Ultimately, folks in and around Orange Beach wound up witnessing hailstones the size of baseballs and softballs, which caused a tremendous amount of damage to vehicles, windows, roofs, and just about anything breakable that was left exposed to the elements that night.

Given the intensity of the supercell required to support such giant hailstones, it's really rare to get this kind of hail so close to the water. In fact, these were the largest hailstones ever recorded in southwestern Alabama—not an easy feat given the region's track record with nasty severe weather outbreaks.

Hail History

Hail that big is rare, period.

The National Weather Service recorded more than 363,000 reports of hail of all sizes between 1955 and 2019, ranging from tiny beads of ice the size of a green pea to grapefruit-size hail that left craters in the ground when it impacted the surface. More than 85,000 of those hailstones measured the size of a golf ball (1.75" in diameter) or larger, accounting for about one-quarter of all the hail reported in the United States.

It's tough for hail to grow larger than that. Only 0.5% of the hail reported in the country during that 64-year period—or a little under 1,800 reports—came in for hail the size of a softball or larger. The map above shows all recorded instances of ≥ 4.00" hail across the United States. The concentration of major hail on Plains sticks out like a sore thumb. The number of reports falls off with distance from the central states.

There are a few instances of huge hail in places you normally wouldn't expect it, such as an exceptionally damaging hailstorm in Miami, Florida, on March 29, 1963, and a powerful supercell in north-central Oregon on July 9, 1995. But while there are some big-time hail reports near the Gulf Coast in Texas and Louisiana, reports of very large hail were non-existent along the Gulf Coast between New Orleans and Key West until a few days ago.

[Radar Images via GR2Analyst]

You can follow me on Twitter or send me an email.

Please consider subscribing to my Patreon. Your support helps me write engaging, hype-free weather coverage—no fretting over ad revenue, no chasing viral clicks. Just the weather.

Please consider subscribing to my Patreon. Your support helps me write engaging, hype-free weather coverage—no fretting over ad revenue, no chasing viral clicks. Just the weather.

0 comments: