Historic disasters have transitioned from a noteworthy abnormality to something that we've come to expect on a regular basis.

Unprecedented heat, devastating fires, destructive flash floods, and rapidly intensifying hurricanes are just the way things are. "Another billion-dollar flash flood? Add it to the two other we've seen this month."

This is going to be a more 'personal' post than I usually write for DAMWeather. I've covered a century's worth of unprecedented weather events in the past couple of years—almost all of it in a straight-news format.

I can't bring myself to do that for Hurricane Otis. I've spent almost two weeks trying (and failing) to write about the scale-topping hurricane that devastated Mexico's Acapulco region on October 24.

There are lots of worst-case scenarios when it comes to weather disasters. Hurricane Otis is one of the only storms in recent years that can legitimately claim the title of a worst-case scenario.

Hurricanes rapidly intensifying as they approach landfall is an alarmingly common disaster these days, and it's a horror that both people and governments still aren't prepared to confront.

Otis unexpected leapfrogged to a category five titan

Otis rapidly intensified from a 50 mph tropical storm to a category five hurricane with 160 mph winds in just 24 hours, and it slammed almost head-on into Acapulco and its 1,000,000+ residents at maximum strength.

Hurricane Otis' explosive growth is one of the most intense rapid intensification events ever observed—beaten only by Hurricane Patricia in 2015, which peaked as the strongest hurricane ever reliably observed when its maximum winds reached 215 mph.

But the experts who dedicate their professional lives to tracking and understanding these atmospheric behemoths were flabbergasted by the hurricane's rapid growth. No forecaster or their computer models foresaw the storm growing into a major hurricane before landfall. The official NHC forecast called for Otis to maybe just barely crack hurricane strength as it crossed the coastline.

So to watch this hurricane run away in the atmospheric chain reaction from hell as it closed in on a heavily populated metro area was truly the 'nightmare scenario,' as an NHC forecaster said in the agency's update declaring the storm a scale-topping category five.

Zona Hotelera pic.twitter.com/88uSt3MqLE

— Grace (@Osocom123) October 27, 2023

The nightmare played out. We may never know exactly how strong the winds got in the heart of the city of more than one million people, but precise wind speeds seem irrelevant given the widespread destruction across the region.

Ten storms in ten years

Otis joined a long list of recent hurricanes that rapidly intensified in the run-up to landfall.

Harvey grew from a tropical depression to a category four storm as it approached Texas in September 2017.

Irma, once a scale-topping category five, rapidly reintensified into a category four when it hit the Florida Keys just two weeks later, keeping most of its power as it hit the state head-on soon after.

|

| Source: NOAA |

Two weeks after that, Maria rapidly intensified into a category four hurricane as it slammed into Puerto Rico.

Hurricane Michael exploded into a category five with 160 mph winds as it hit the Florida Panhandle in October 2018.

During the historic 2020 hurricane season, Laura quickly intensified into a 150 mph hurricane as it walloped southwestern Louisiana, barely losing strength at first as it drew energy from the swampy, surge-covered land. Exactly one year later, Hurricane Ida did the exact same thing as it hit southeastern Louisiana.

A year after that, Hurricane Ian intensified into a category five storm just before making landfall in southwestern Florida. The storm's destructive wind and surge killed more than 100 people, making it Florida's deadliest hurricane in a century.

This past August, Hurricane Idalia rapidly intensified in the eastern Gulf of Mexico and hit the Florida Panhandle as a category three storm. It was the strongest storm ever recorded at landfall in this part of the state.

That's just Atlantic hurricanes that revved up as they closed in on shore. There have been plenty of storms that rapidly intensified out to sea, and it doesn't even cover the storms—like Otis and unparalleled Hurricane Patricia from 2015—we've seen follow this trend in the eastern Pacific Ocean, or in the world's other tropical basins.

Consistently warm waters fuel rapid intensification trends

We've seen a tremendous stretch of unprecedented warmth across almost the entire Atlantic basin this year. It's the reason we've seen 20 tropical storms and hurricanes this year despite a strong El Niño over in the eastern Pacific.

The destructive wind shear generated by El Niño typically shreds apart any attempted tropical cyclones over the Atlantic. But sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic are so warm that any disturbance had the opportunity to develop—and they took full advantage of that unusual environment.

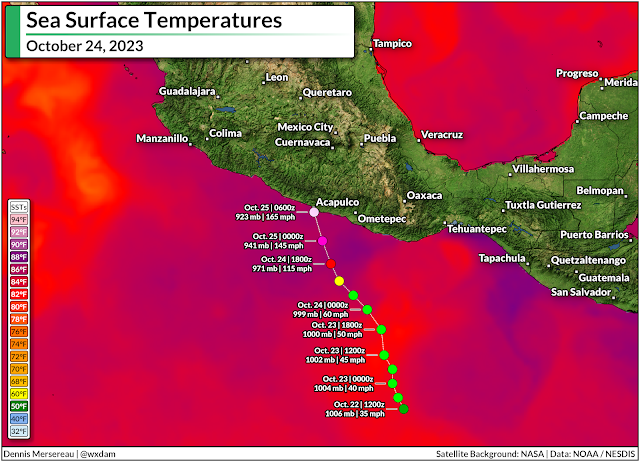

We can even see the influence of freakishly warm water when it comes to these eastern Pacific storms. Water temperatures off the western coast of Mexico were unusually warm when Hurricane Otis tracked over the region. Overlay the storm's track on top of a map of sea surface temperatures and it's easy to see a major reason that storm surpassed the most aggressive forecasts.

Time and time again, exceptionally warm sea surface temperatures are the driving force behind these rapid intensification events. It's not the whole story—a nearby jet stream improved Otis' outflow, for example, helping the hurricane strengthen in hyperdrive—but the freakish warmth in the Atlantic in recent years, and this year in particular, is a worrisome data point when it comes to future storms.

As the planet and its oceans continue to warm, we may have to contend with more of these sudden rapid intensification events in the future, including as storms snake toward landfall.

That's downright terrifying when so many communities seem incapable of preparing for a storm they have a week to see coming. I recently wrote about our "strained attention economy" as a major reason so many well-advertised disasters seem to hit people by complete surprise. I am not confident that most people or community leaders are prepared for 'average' hurricanes, let alone these monstrous storms that ramp up within hours of landfall.

We've seen an entire lifetime's worth of tropical devastation from a handful of storms in the past couple of years. This year's amped-up storms won't be the last ones we see. At the very least, it's a strong argument to pay incredibly close attention to the weather during hurricane season, as the storm you went to sleep watching might not be the same one staring you down when you wake up.

0 comments: