Hurricane warnings are up for portions of the Lesser Antilles this weekend as an unlikely storm lashes the region with high winds and heavy rainfall.

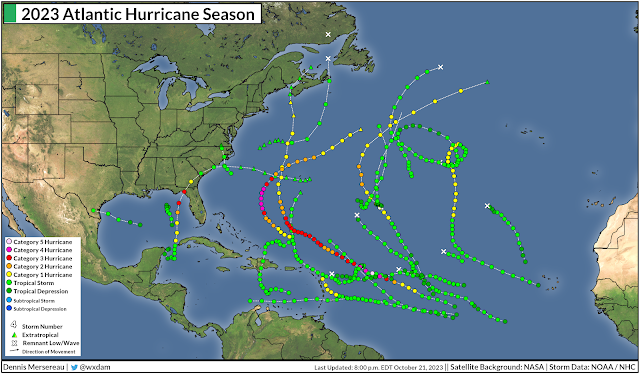

Hurricane Tammy is our 20th named storm of this remarkable hurricane season. It's noteworthy to have that many named storms in any circumstances—2023 is now tied for fourth-most active Atlantic hurricane season on record—but we're in the midst of a strong El Niño, which typically stifles tropical cyclone activity across the Atlantic.

Tammy Makes Twenty

We've had 20 nameable storms across the Atlantic Ocean so far this season. The first system was an unnamed subtropical storm that forecasters added to the record in a reanalysis of the event a few months later.

Seven of the storms grew into hurricanes, and three of those storms—Franklin, Idalia, and Lee—managed to balloon into major hurricanes. Even more impressive is that Lee briefly grew into a category five storm, one of only a few dozen ever recorded over the ocean basin.

Tropical activity in the Atlantic typically slows down and moves closer to the Caribbean and Gulf as we head into October, but Tammy is especially unusual because it's a full-blown hurricane with roots in a tropical disturbance that originated over sub-Saharan Africa.

El Niño Strongly Influences Atlantic Hurricanes

The eastern Pacific Ocean around the equator is usually pretty chilly due to upwelling of frigid waters from deep within the ocean. Easterly winds blowing across the equatorial Pacific push warm surface waters toward Australia, strengthening the upwelling off South America as waters rise from below to fill the void.When those easterly winds weaken or reverse direction, however, that warm surface water floods back toward South America. These warmer waters of an El Niño aren't much—just a couple of degrees—but it's enough to significantly affect the atmosphere in ways that have far-reaching effects from Asia to Africa.

|

| Source: NOAA Data Snapshot |

Even though El Niño's effects are most noticeable during the winter, these unusually warm waters can beef-up thunderstorm activity across the eastern Pacific—creating wind shear that blows east over the Atlantic Ocean. This wind shear is (usually) destructive to any budding tropical cyclones over the Atlantic, putting an end to them before they have a chance to flourish.

That's usually how things go. The 1991 and 1992 hurricane seasons were relatively quiet due to a lengthy El Niño. 1991 only saw eight named storms, while 1992's first named storm—the infamous Hurricane Andrew—didn't form until the end of August.

The last underactive hurricane season we saw in the Atlantic took place at the tail-end of a strong El Niño in 2015, when only 11 named storms managed to form.

2023 Breaks The Rules

This year should've followed suit. A strengthening El Niño over the eastern Pacific normally would've put a lid on the Atlantic Ocean this year, stifling most opportunities for storms to develop.

That very much didn't happen. But why?

Forecasters knew in advance that we might be in for a trend-bucking season before it even began.

"El Nino’s potential influence on storm development could be offset by favorable conditions local to the tropical Atlantic Basin," NOAA wrote in its initial seasonal outlook published back in May.

The factors they outlined in their forecast pretty much came to pass. Sub-Saharan Africa saw a fruitful monsoon season this summer and fall, which pumped one disturbance after another into the eastern Atlantic Ocean.

Sea surface temperatures across the Atlantic have been historically warm so far this year, as well. The increase in disturbances, combined with the mind-boggling heat across the entire basin, afforded more opportunities for systems to develop and thrive.

For all the activity we've seen, El Niño did still flex its muscles. Many of the storms we've seen this year were relatively weak, largely struggling with destructive wind shear that's characteristic of El Niño years.

But those favorable factors around the Atlantic basin combined to overpower El Niño and cement 2023's spot in the history books as one of the most productive hurricane seasons ever witnessed. And it's not quite over yet. It's not out of the question that we could see another couple of storms over the next month or so.

There are only two names left on this year's list. If we use those names and require a 23rd name, the National Hurricane Center would dive into the new supplemental list of names, beginning with Adria. This supplemental list replaced the use of Greek letters to name excess storms, a change made after the hyperactive (and at times confusing) 2020 hurricane season.

[Satellite image via NOAA]

0 comments: