Tropical Storm Erin formed off the Cabo Verde Islands on Monday. The storm is set to become the first hurricane—and possibly the first major hurricane—of the 2025 Atlantic season later this week.

A vigorous tropical wave rolling off the coast of Africa got its act together in a hurry as it emerged over the warm waters of the eastern Atlantic Ocean, quickly organizing into the season's fifth named storm.

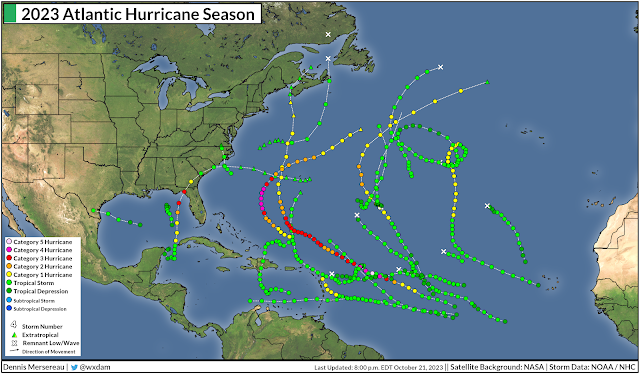

Like all storms that originate in the Cabo Verde region, this is going to be an 8-10+ day marathon watching this storm march west across the Atlantic basin.

Environmental conditions are favorable for steady intensification in the days to come.

The National Hurricane Center expects Erin to gradually strengthen over the next five days, with the agency's forecast explicitly calling for a major hurricane in the central Atlantic by Wednesday.

These long-duration storms cause quite the anxiety spike among coastal residents who are constantly refreshing weather pages in hopes of learning more about the system's next move.

Unfortunately, it's far too soon to say exactly where the storm will track beyond next weekend. We can look at signals in the models to get an idea of where it may track beyond the end of the NHC's five-day forecast.

Most tropical storms and hurricanes in the Atlantic are steered along by large ridges of high pressure parked over the center of the ocean. The strength and placement of these highs dictate how far west they travel before they begin to recurve. (Some storms don't recurve at all.)

|

| A model image showing ridges and troughs in the upper atmosphere on Friday evening. SOURCE: Tropical Tidbits |

A stronger high-pressure system will allow the system to move farther west, posing a greater threat to the U.S. and Atlantic Canada. A weaker high provides more opportunities for the storm to recurve north and out to sea.

Right now, signals in the models show decent odds that a weaker high will probably allow Erin to recurve and track near Bermuda before turning out to sea. However, there's plenty of time for things to change. Very small changes in the near-term can have big long-term effects in a storm's track.

We're coming up on the peak of hurricane season. Tropical Storm Erin's impending marathon is a good reminder that folks who live in coastal states and provinces should be ready for storms well before a threat is on the horizon.

[Satellite image courtesy of NOAA.]

Follow me on Facebook | Bluesky | Instagram

Get in touch! Send me an email.

Please consider subscribing to my Patreon. Your support helps me write engaging, hype-free weather coverage—no fretting over ad revenue, no chasing viral clicks. Just the weather.

Get in touch! Send me an email.

Please consider subscribing to my Patreon. Your support helps me write engaging, hype-free weather coverage—no fretting over ad revenue, no chasing viral clicks. Just the weather.